Dr Helen Scales’ top 5 fish (and other sea life)

The question I’m asked most often when I visit schools and give public talks is an excellent one, but I have a tough time answering it: what is your favourite sea creature? Thankfully, writing this book I had the chance to pick 80 of my favourite species from the ocean, although even that was tough — there are so many to choose from. Eventually I narrowed it down, setting myself various rules. I wanted to take readers on a global tour through all the different parts of the ocean, from the icy polar seas, to the deepest ocean trenches and everywhere in between. I wanted to introduce readers to animals they may never have heard of, and tell them new things about the more familiar creatures that inhabit the salty waters around the planet. And I wanted to trace the connections that run between ocean species and the lives of people around the world. Out of my 80 fish and other sea life, here are five I am especially fond of.

Ninja lanternsharks

I have a real soft spot for deep-sea animals that glow in the dark — and there’s a lot of them. Roughly three quarters of species that live in open waters down in the dark depths are bioluminescent and have the ability to light up parts of their body. Among them all, one of my absolute favourites is this little shark (you could easily cradle one in your arms). Ninja lanternsharks have inky black skin and pores across their belly that light up blue, probably to help hide their silhouettes when seen from below against the blue light trickling down from the sea surface, so they can sneak around unseen ninja-like. They were discovered by the amazing marine biologist Vicky Vasquez, and it was her young cousin who suggested the name.

Bowhead whales

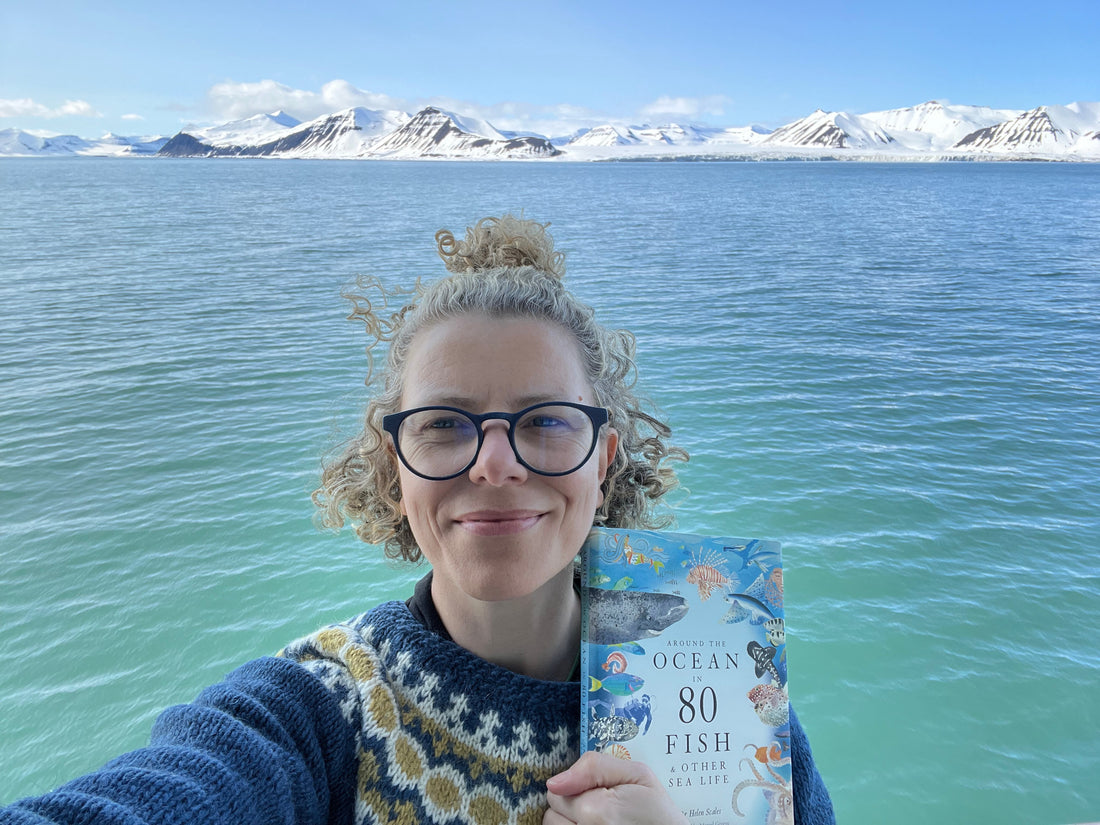

I recently had the chance to visit the icy realm of several species featured in the book. Sailing around the Svalbard archipelago was the furthest north I’ve ever been and my first time in polar seas. I was completely blown away by the beauty of it all. In the end I didn’t actually see any bowhead whales — the only whales that live full time in the freezing waters of the Arctic — but I was good knowing they were out there somewhere, singing songs to each other. At one point I had the chance to jump (briefly!) into the Arctic Sea so I know just how cold it is, and have a whole new appreciation for the incredible adaptations that allow these marine mammals to survive in the Arctic, including all through the long dark winter. Bowhead whales are so well insulated with thick blubber they could overheat while swimming, so they sometimes swim around with their mouths open to cool down.

Common cuttlefish

One reason I love cuttlefish is that they are masters of delayed gratification (as am I!). When offered a tasty morsel right away or the promise of an even tastier treat if they wait a while, they learn that it’s worth hanging on. They even turn their backs on the first offering, to avoid temptation. This is a version of the marshmallow test in which young humans are offered either one sweet treat now, or two if they wait. It turns out the cuttlefish perform better than children (cuttlefish are offered crab and shrimp, not marshmallows).

Sawfish

Even though us humans live on land and we can only pay short visits to the ocean, there are all sorts of links between people and the sea. Many of the species I picked for the book reveal these close connections, including sawfish. For thousands of years, people have embraced these formidable looking animals as symbols of war and power, protection and good fortune. Their saw-shaped nose pieces were left tombs in the Aztec empire, they’ve been used as traditional weapons around the world including in the Philippines and Papua New Guinea, and they appear on the currency used today across West Africa.

Walking sharks

It’s not true that sharks have to keep moving to breathe. Some do, like the fast-swimming mako sharks, but plenty of sharks live a far more sedentary life, lying still on the seabed. Walking sharks take this to an extreme and can hold their breath for more than an hour while they walk out of the sea, using their fins as legs, and go hunting for prey in tide pools. Sharks have existed for at least 450 million years and walking sharks are the newest shark species — they evolved in the last two million years.